What can a hapless church choir teach us about storytelling?

I belong to a small church choir. Our choir director, V, describes our talents thusly:

“We don’t sing because we’re ready. We sing because it’s Sunday morning at 11 am.”

Recently, our hopeful but hapless choir attempted to learn to hum. This is harder than it sounds! We were performing a spiritual, and there was a humming section in the bridge, but every time our inexperienced voices tackled the hum, it came out like we were a batch of ghosts.

Woooooooo, we crooned, with an apparent intention to haunt the services on Sunday.

Our choir director stopped us. “Not woooo,” she said, face brave as ever. “You don’t want to make a woo-woo sound. Press your lips together.”

With this dictum in mind, when we hit the bridge, our choir became mute. Literally no sound could emerge from our compressed lips.

She stopped us again. “Make a little space,” she said. “Part your teeth.” And she kept attempting to teach us how to hum.

“Open your throat.”

“Press your tongue against the base of your mouth.”

Pretty soon we sounded like a bunch of people trapped in a dentist’s chair, or perhaps a troubled hound dog, as we struggled to make some kind of sound while trying to contort our mouths in the proper humming position.

And then R stepped in. R is one of our talented vocalists, a tall African American man who has been singing in the choir since 1979 and grins with joy whenever he hits a low note.

“Think of it like you’re moaning,” he said. “It’s a spiritual. Just moan with sorrow.”

And boom. Suddenly the room was filled with the sound of sorrowful humming. We performed the anthem on Sunday at 11, and when we came to the bridge, we filled the sanctuary with soulful, harmonizing moans.

This is a classic example of what Daniel Kahneman calls “fast” and “slow” thinking, and it explains the difference between two-dimensional communications and storytelling.

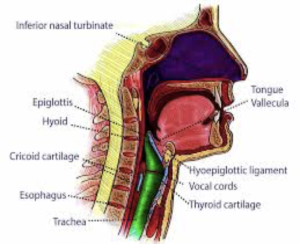

When you’re giving your audience facts and statistics, you’re trying to teach them to sing by telling them how the throat works

Our choir director was using System Two thinking, “slow” thinking, to teach us how to hum. She was giving us the technical, rational directions on how to move our lips and tongue and throat to produce an on-key humming sound that could carry across a huge sanctuary. She was tapping into our rational, analytical brains.

But people do not tend to make new connections through System Two. System Two is good for deep analysis, but change doesn’t begin with deep analysis. Change begins in a more emotional, intuitive way. It starts with a feeling. John Kotter’s work shows this as well. We don’t analyze, think, and change. We see, feel, and change.

People respond when you focus first on how the music makes them feel.

When R made us feel sorrow, he tapped into “fast” thinking, into System One, our emotional, instinctive brains. With just a simple sentence that tapped into an emotional experience, every member of the choir was able to connect instinctively to the techniques that V was trying to teach.

We couldn’t learn the technical moves on our own. We literally went mute with effort. But when R connected the technical instructions to an emotional state, when he showed us what to feel, the room was filled with humming.

That’s how change works outside of the choir loft as well. So often, when we want people to do something, we try to give them technical details, as our choir director did. Whether the issue is policy change, or health information, we start quoting statistics, arcane details. We start giving anatomy lessons.

And then we get frustrated, as V surely did, when our audience can’t hit the notes.

But there is a simple way to get around this problem. What people really need is to be given an emotional state. Help us feel something. Think about what your story feels like. Is this a hopeful story? What will it feel like, when your cause is met? How does it feel right now, when we’re struggling? Every time you connect to one of the senses, every time you connect it to an emotional experience, our brain lights up and our energy kicks in.

When you give us facts and statistics, our brains shut down and our song gets strangled. But give us a story to connect to — even a story as simple as “it’s a mournful song, just moan” — and the room will fill with music.